Luca Signorelli in Orvieto Cathedral: the muscular apocalypse that outclasses Hollywood

- The Introvert Traveler

- Sep 3, 2025

- 3 min read

Last visit: October 2020

My rating: 9/10

Duration of visit: half an hour

Stepping into the Chapel of San Brizio in Orvieto Cathedral is a bit like channel-surfing between a Zack Snyder movie and a medieval theology treatise. Only here, it’s all frescoed, all Renaissance, and all gloriously over the top. Forget the Marvel Cinematic Universe: Luca Signorelli, armed with brush and pigments, throws in our faces the most spectacular end of the world ever conceived by a human being with artistic ambitions and a bodybuilder complex.

Luca Signorelli: the man who loved abs too much

Born in Cortona, with a suspicious fondness for artistic gymnastics (and perhaps a side interest in dissection-room anatomy), Luca Signorelli wasn’t just an artist—he was the Apocalypse’s personal trainer. Raised in the school of Piero della Francesca—the painter who disciplined perspective like a Marine drill sergeant—Signorelli came to Orvieto with one single, clear, unshakable mission: to make every other painter look like a flabby amateur. And for a while, he succeeded.

Orvieto Cathedral: psychedelic Gothic with threats of eternal damnation

Let’s get one thing straight: Orvieto Cathedral was already completely over the top before Signorelli even set foot inside. A Gothic spaceship anchored among the Umbrian hills, all gilded pinnacles, blinding mosaics, and bas-reliefs that look like they were carved by a band of possessed friars after binge-reading Dante on acid. You know the façade? A delirium of polychrome marble and horror-movie detail: there are souls writhing in infernal torment right there on the entrance, as if to say, “If you come in here, be warned. We’re not joking.” There’s a Last Judgment etched in stone that would make even Hieronymus Bosch feel uncomfortable. So you wonder: what more could possibly be added to such magnificence? The answer is simple: a visual bomb named Luca Signorelli, who with his frescoes turned the cathedral’s interior into a cosmic theater where sin, resurrection, and abdominal muscles are the absolute stars. If the Cathedral once inspired awe, with Signorelli it also started raising an eyebrow. And flexing.

A Renaissance on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown

Year of Our Lord 1499: Savonarola has just been roasted, and the smoky aftertaste of that great barbecue still lingers somewhere between Tuscany and Umbria; Italy is a place where every two weeks there’s either a war, a plague, or a comet announcing the Antichrist. In short, the perfect atmosphere for decorating a chapel with scenes of death, resurrection, and eternal damnation. After Fra Angelico—the gentle painter who saw angels everywhere—had left the job half-finished (perhaps too sugary for such troubled times), the Cathedral Chapter calls in Signorelli. And he doesn’t back down: in flawless 16th-century Tuscan he basically says, “Hold my wine, I’ll show them what Hell really looks like.” He accepts, cracks his knuckles, rolls up his sleeves, and starts painting Hell as if he were about to spend his summer holidays there.

Muscles, Grimaces, and Resurrections: Welcome to the Afterlife Gym

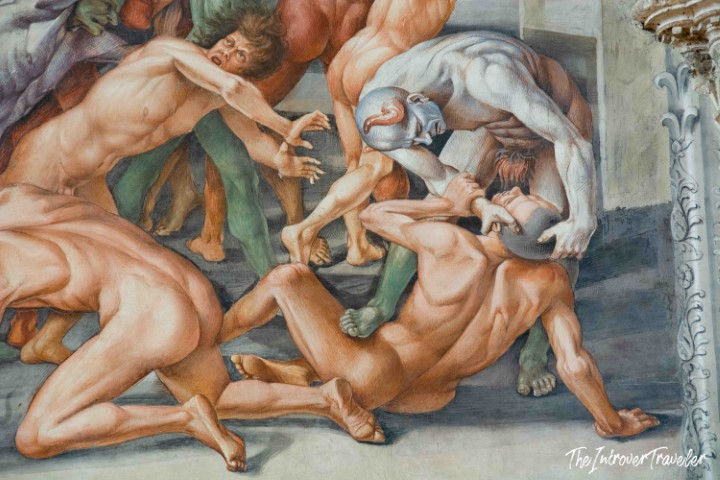

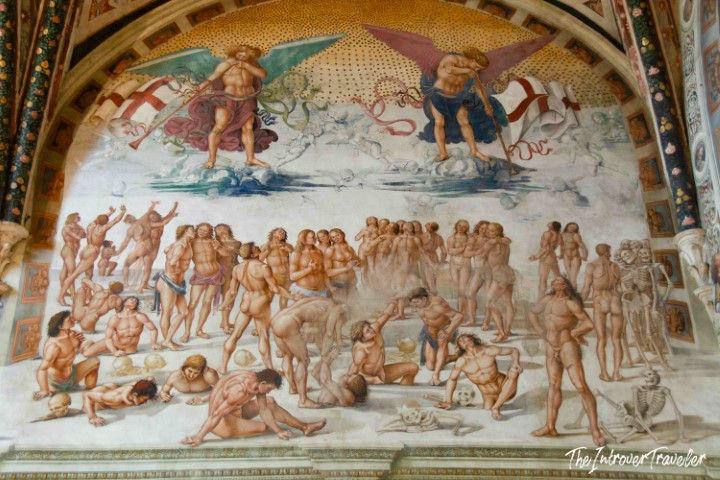

You know the Resurrection of the Flesh? Forget sweet Madonnas and composed saints: here, the dead peel themselves out of the ground like Hulk after a nuclear nap, lift their heads, crack their joints, and look ready to sign up for an otherworldly CrossFit class. The angels? They move like Cirque du Soleil acrobats. The demons? Straight out of a rave in the abyss. Every inch of the chapel screams hyperbole, testosterone, sweat, flesh, and eternal fate.

Painting here is no longer just painting: it’s an explosion of naked bodies—foreshortened, twisted, knotted—more complicated than a sailor’s knot tied drunk. But beneath the muscular bravado, there’s an obsession with sin, redemption, and looming ruin: this is the Renaissance beginning to understand that man is not only the measure of all things, but also the measure of all disasters.

From Dante to Michelangelo (With a Stopover in Demonic Invasion)

Signorelli didn’t invent everything from scratch: he looked at Giotto, read Dante, got hooked on the Apocalypse of John, and then said, “Okay, let’s do it better.” He added six kilos of muscle to every figure, cranked the pathos up to deafening levels, and left an indelible mark on Italian painting.

And Michelangelo? Oh yes. That Michelangelo. The guy who would later decorate the Sistine Chapel as if it were the ceiling of his own living room. Well: without Signorelli, Buonarroti’s Last Judgment would have looked like a high school art class end-of-year play. Vasari puts it bluntly: Michelangelo took notes in Orvieto. And who are we to argue?

Conclusion? If you haven’t yet seen Luca Signorelli’s frescoes in Orvieto, you’re missing out on the only serious crossover between bodybuilding, medieval spirituality, and the Sistine Chapel prequel. Bring a chair, open your eyes wide, and let yourself be hit by the power of a man who turned painting into a wrestling match between soul and body. Amen.

Comments