The secrets of the Perseus statue by Benvenuto Cellini in Florence: A Renaissance Masterpiece of Power and Precision

- The Introvert Traveler

- Sep 25, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 18

There is perhaps no place in Florence that represents the overwhelming artistic wealth of this city more than this one, a place so immeasurable that it often goes unnoticed by most of the tourists who flock to this treasure of Italy and humanity every day.

I am referring to the Loggia de' Lanzi; this small portico is a true paradox in the history of art. Its location, between Piazza della Signoria, the replica of Michelangelo's David, and the Uffizi Gallery, causes most of the millions of people who pass by each year to overlook it, using its steps mainly to rest their tired legs. Some might wonder why all those statues are exposed to the elements without any form of protection, quickly concluding that they must be low-value copies, just like the replica of David, which is only a few steps away. And herein lies the paradox: Florence is a city so brazenly rich in art that it can afford to display and concentrate in a public space a dozen masterpieces that, anywhere else in the world, would enjoy a place of prominence inside a museum; and the concentration is so great that it leads most observers to neglect them.

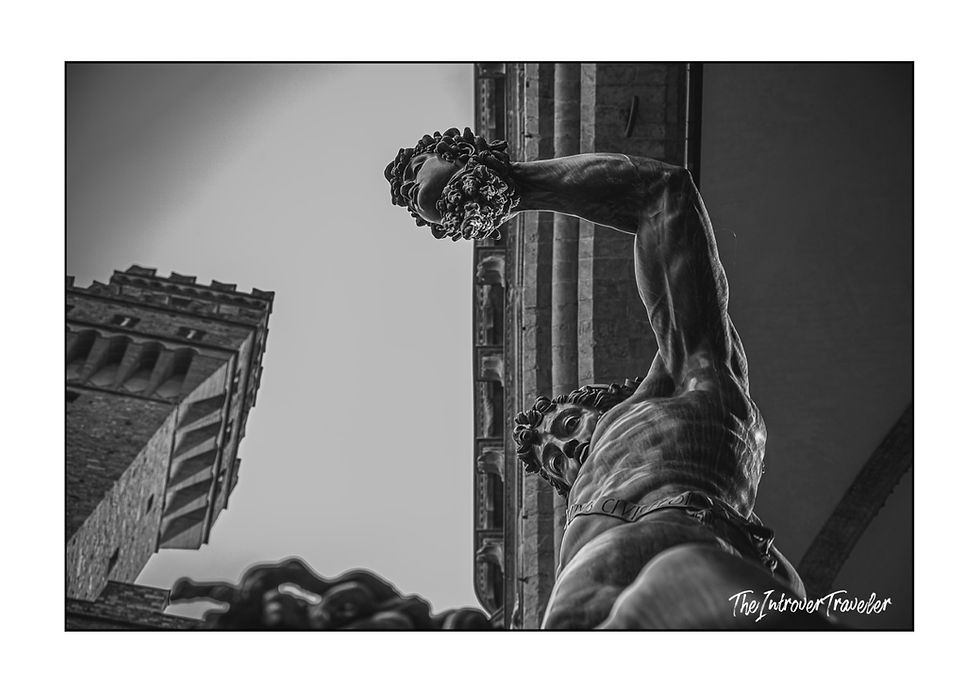

Among these works, each more formidable than the next, the most sensational of all is, probably, Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus statue, a masterpiece of overwhelming expressive power, sensuality, and technical mastery.

The Majesty of Benvenuto Cellini's Perseus: A Masterpiece of Renaissance Sculpture

When standing before Benvenuto Cellini 's Perseus statue, located under the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, one is overcome by a sense of awe. This sculpture not only embodies the triumph of Renaissance art but also reflects the troubled history of a man whose genius was matched only by his passion. Cellini, a master of bronze casting, brought to life a work that merges myth, power, and technique with incredible force. Perseus is not just an artistic masterpiece; it is a testament to the courage, determination, and skill of a man, representing one of the pinnacles of Renaissance sculpture.

Benvenuto Cellini: The Impetuous Genius of the Renaissance

To fully understand the value of the Perseus, one must know its creator. Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) was not just a sculptor; he was a Renaissance man in the truest sense of the term, a goldsmith, musician, adventurer, soldier, and writer. Born in Florence, his life was marked by constant conflicts, rivalries, and travels, but also by an immense desire to assert himself through art. The autobiography he left us is a captivating read (whic I strongly recommend), filled with episodes that blend his private life with his artistic endeavors, often narrated with an exaggerated and narcissistic tone, but no less fascinating for that.

Cellini was not an easy character. He was known for his impulsive, often irritable, and quarrelsome nature. He was no stranger to conflicts with authorities and rivals, and his life is filled with duels, imprisonments, and daring escapes; during the "Sack of Rome" he defended Castel Sant'Angelo by killing Charles III of Bourbon and wounding the Prince of Orange (or at least, that is what he claimed in his autobiography). However, he was also endowed with extraordinary talent, which allowed him to rise as one of the greatest artists of his time. Beyond his technical skill, Cellini was a man capable of thinking outside the box, always in pursuit of perfection and ready to overcome challenges that would have discouraged many others.

The Casting of the Cellini's Perseus statue: A Triumph Over Adversity

A crucial episode in Cellini's career, and in the creation of the Perseus, is the harrowing account of the statue's casting, which Cellini vividly describes in dramatic detail in his autobiography. The bronze casting process, incredibly complex and fraught with risk, became a veritable nightmare. After meticulously preparing the wax model of the statue, the next step was the casting: replacing the wax with molten bronze to shape the final sculpture. During this phase, which had to be carried out in a single casting, Cellini faced a series of technical difficulties, as well as physical and psychological challenges.

Cellini recounts that during the casting, the furnace malfunctioned, the bronze wasn’t melting as expected, and the situation seemed dire. In a state of despair and feverish agitation, on the verge of delirium, the artist found himself faced with a dilemma: abandon everything and accept defeat, or find an immediate solution. Cellini nearly gives up and withdraws to his bed, but then inspiration strikes him: he ordered his assistants to throw copper plates and kitchenware into the furnace to raise the temperature and save the casting. Despite the chaos and the challenges, Cellini’s desperate plan worked, and he successfully completed the casting.

This episode, described so vividly and in such detail, symbolizes his tenacity and his ability to overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles. The Perseus emerged from this casting as a work of extraordinary beauty and power, with a fluidity and precision that only a master like Cellini could have achieved. Under his hands, the bronze transformed into flesh and taut muscles at the moment of the mythological hero’s triumph.

Perseus: A Masterpiece of Technique and Symbolism

The Perseus, completed in 1554 and standing 519 cm tall, is above all a political work. Commissioned by Cosimo I de’ Medici, it was conceived as a visual declaration of the Duke’s authority over republican chaos. Perseus raising the severed head of Medusa is not merely a mythological hero, but an allegorical bringer of order—a symbol of the slaying of the monster of anarchy. As Charles Dempsey has noted, the Gorgon represents the perils of the former republican regime, and Cellini, through his gleaming bronze, celebrates the new ducal absolutism under the guise of the classical hero.

The statue depicts the Greek hero holding aloft the decapitated head of Medusa, the monster whose gaze turned all who looked at her to stone. The sculpture is a masterpiece of balance and dynamism: Perseus’s body, nude and perfectly proportioned, is taut in the act of triumph, while the hero’s face retains a superhuman calm. The contrast between the serenity of Perseus and the violence of the beheading, visible in the gruesome details of Medusa’s severed head, creates a powerful emotional impact.

The complexity of the statue lies not only in its height (over five meters including the base), but also in the multiplicity of viewpoints, in the burnished surfaces, and in the serpentine torsion of the figure, features that reflect the stylistic traits of Florentine Mannerism, updated through the influence of Michelangelo, yet already projecting toward the compositional eloquence of the seventeenth century.

Cellini constructs a powerfully rhetorical iconography. Perseus is nude, youthful, idealized, with a stern and impassive expression. He stands on a pedestal adorned with narrative reliefs (depicting the story of Andromeda and Perseus), and tramples the decapitated corpse of Medusa, whose blood congeals into serpents. The severed head is raised in triumph—a theatrical gesture, frozen in an exclamatory verticality, which imposes a frontal perspectival viewpoint on the observer, but also demands interpretive circularity, as the work is meant to be viewed in the round.

Cellini breaks with the classical tradition of Medusa as a monstrous figure. Her face is not horrific, but tragically beautiful, almost marble-like, marked by a stunned sorrow. It is here that the tragic soul of the work emerges: in the superimposition of the horror of death and sublime aesthetics, the terribilità of Florentine art is transposed into metal.

As Georges Didi-Huberman has argued, Cellini’s Medusa embodies the instant of death as a frozen gaze: she is the icon of the gaze that kills and is killed. In this sense, the work is also a meta-reflection on the power of art: just as the gaze of the Gorgon petrifies, so too is the viewer’s gaze captured — immobilized — by the terrible beauty of the sculpture.

The Loggia de' Lanzi: An Open Air Museum

The context in which Perseus is placed is equally fascinating. The Loggia dei Lanzi, located in Piazza della Signoria in Florence, is an open-air museum in its own right. Built at the end of the 14th century to host public ceremonies and assemblies of the Florentine government, the Loggia eventually became a space dedicated to the celebration of art and power. Its elegant arches provide the perfect setting for a series of sculptures representing the finest examples of Renaissance and Baroque art.

Among the most famous sculptures displayed under the Loggia, in addition to Cellini’s Perseus, is Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabine Women, another Renaissance masterpiece. However, it is Perseus that dominates the scene, thanks to its central position and the sheer power of its message. The Loggia dei Lanzi is not merely a place of exhibition but a symbol of the continuity between civic power and the artistic grandeur of Florence.

The presence of Perseus in this prominent location underscores the connection between art and political authority, reinforcing the idea that Florence, under the Medici, was a city of both artistic excellence and strong governance. Cellini’s sculpture, positioned in such a historical and civic space, becomes an emblem of Florence’s cultural and political legacy.

The Importance of Cellini in Art History

Benvenuto Cellini is a key figure in the history of Renaissance art. His mastery of bronze casting, his exceptional skill in goldsmithing (remember, he was also a master in engraving jewelry), and his ability to blend myth and technique make him a unique artist. Perseus stands as one of the highest expressions of his artistic prowess, but his contributions to other forms of art should not be overlooked.

Moreover, his autobiography is one of the most fascinating texts of the Renaissance. It not only offers a broad view of daily life, as well as the political and social events of his time, but it also allows us to enter the mind of an artist who lived his art as a personal mission. Every success, every challenge overcome, is narrated with a passion that reflects his impetuous temperament and his pride.

Perseus as an Icon of Florence

Today, Cellini’s Perseus is one of the most beloved works by the Florentines. It stands not only as an extraordinary testament to its creator’s technical mastery but also as a symbol of the power, beauty, and artistic innovation that define Florence. Its presence under the Loggia dei Lanzi, constantly in dialogue with Michelangelo’s David and the other sculptures in the piazza, transforms the city into a living museum, a place where the past and present intersect in a continuous exchange of meanings.

In conclusion, the Perseus statue by Benvenuto Cellini is far more than a mere sculpture. It is a work that tells a story of struggle and triumph, of technique and passion, of myth and reality. It stands as a testament to the greatness of an artist who, despite his human flaws, managed to leave an indelible mark on the history of art. For this reason, when standing before this masterpiece, one cannot help but feel captivated and grateful to behold such a powerful and beautiful creation, born from the genius of an extraordinary man.

If you are planning a trip to Florence, you may be interested in these posts.

Film location

The Loggia dei Lanzi was the setting for one of the main scenes in A Room with a View by James Ivory.

If you are fond of Benvenuto Cellini’s works, I would recommend the definitive book on his art by John Pope-Hennessy; to this, of course, must be added his splendid autobiography.

Comments