The Egyptian Museum in Cairo's Tahrir Square: Wonders and Inadequacies

- The Introvert Traveler

- Sep 16, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2025

Giorgio Manganelli: "You'll excuse me: I really don't know how to address you..." Tutankhamun: "Do you feel you should address me?"

Giorgio Manganelli, Le interviste impossibili, Milan, Adelphi, 1997

Last visit : August 2025

My rating : 8 for the museum, MUST SEE for Tutankhamun

Visit duration : 4 hours

Disclaimer : This is an "instant obsolete" post. The Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square, which for a century has been a leading global cultural institution, is expected to hand over its operations to the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza in a few weeks (currently rumored to be November 1st).

News about the historic museum's future is currently conflicting; it's almost certain that it will remain open, continuing to display numerous works that have been locked away in storage for decades, unable to find a suitable exhibition space. However, it's likely that it will no longer attract the large crowds of tourists and travelers it once attracted. From some articles I've read online, it seems the relocation of Tutankhamun's golden mask is still uncertain, as its transfer would be subject to Egyptian law. If that were the case, the old Cairo museum obviously faces a bright eternity. However, if King Tut's treasure were to be transferred entirely to the new museum, the old museum would become more of a refuge for professional archaeologists and enthusiasts, seeing the large crowds disappear from its corridors forever.

A foundation linked to the pioneering era of Egyptian archaeology

The museum was inaugurated in 1902, at the height of the colonial period, when Egypt was formally under Ottoman sovereignty but effectively administered by the British. The building's construction, entrusted to the French architect Marcel Dourgnon, occurred at a time when Egyptian archaeology was not only a scientific discipline but also a powerful instrument of political and cultural prestige. After decades of excavations, often conducted in a predatory manner by European missions, the idea of providing Egypt with a national museum gradually gained ground, capable of preserving and showcasing its antiquities without them being dispersed to the museums of London, Paris, or Berlin.

The building, in a sober neoclassical style, was conceived as a large, functional container, devoid of Orientalist decorative frills. This reflected a specific choice: to offer a "modern" museum, in keeping with Western standards, and thus place Egypt within the international circle of cultured nations that recognized the monumentality of nineteenth-century museums. The Tahrir Museum, from the outset, was a political gesture: declaring that ancient Egypt was not merely a European image, but, above all, the heritage of the country that had created it.

The role of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo in the history of archaeology

During the twentieth century, the Egyptian Museum became one of the great repositories of pharaonic memory. It was here that the fruits of epochal missions converged: consider, for example, Howard Carter's discovery of Tutankhamun's tomb in 1922. The treasure, destined to remain in Egypt, was placed almost entirely in the museum's halls and remains its main attraction to this day.

The Egyptian Museum was never an ordinary museum. Rather than an exhibition designed for the general public, it was a gigantic organized warehouse, stacked with sarcophagi, statues, stelae, papyrus, jewelry, and mummies. The quantity of artifacts is immense: over 120,000 pieces, many of which are not visible to the public.

The museum's role, however, should not be viewed solely in a scientific light. It represented a laboratory of Egyptian modernity. Nationalist elites in the 1920s and 1930s saw in ancient Egypt a symbol of historical continuity capable of asserting autonomy from the West and legitimizing the construction of a modern state. Thus, the pharaonic collection became a political argument: tangible proof that Egypt possessed a millennia-old civilization, both prior and superior to that of any colonizer.

The Museum and the Arab Spring: A Symbol in Danger

One of the most dramatic moments in the museum's recent history occurred in January 2011, when Tahrir Square became the beating heart of the revolution that would lead to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak. Reports describe a turbulent night, during which gangs of looters entered the building, damaging display cases and stealing several artifacts.

The museum was in serious danger of destruction. Only the intervention of citizen volunteers, who formed a sort of human cordon around the building, prevented further damage. Images of the shattered display cases and mutilated statues traveled around the world, an eloquent symbol of the vulnerability of cultural heritage in times of political crisis.

The museum emerged from that episode with not only material but also symbolic wounds. Its integrity was no longer guaranteed; its identity-building function was being challenged by the chaos in the square. For many international observers, the affair revealed how fragile heritage protection was in Egypt, in a context marked by corruption, lack of funding, and political instability.

The handover at the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM)

With the new millennium, it became increasingly clear that the Tahrir Museum was no longer adequate to house the pharaonic collection. The spaces were saturated, the conservation conditions problematic, the museographic standards obsolete. Thus was born the idea of the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) , a gigantic construction project begun near the Pyramids of Giza, intended to become the largest archaeological museum in the world.

The GEM, whose official inauguration has been postponed several times (a common fate for many large Egyptian projects), represents a sort of symbolic transfer of capital: from the ancient 19th-century building in the city center to a new monumental structure, designed according to contemporary museum standards. Tutankhamun's entire treasure is expected to be moved there, along with thousands of artifacts currently stored in Tahrir's warehouses.

However, the prospect is not without contradictions. While the GEM promises cutting-edge conservation technologies and an immersive museum experience, it also signals an impoverishment for the Tahrir Square museum, which risks becoming a residual institution. Many Egyptians fear that the ancient museum, stripped of its most celebrated collections, will lose its prestige and be reduced to a sort of secondary antechamber to the GEM.

The main artefacts

Among the countless works preserved in the Tahrir Museum, some deserve particular mention, not only for their beauty, but also for the symbolic value they have assumed in the history of archaeology.

Tutankhamun's treasure: the world-famous funerary treasure, consisting of thousands of objects, including the magnificent golden mask and anthropomorphic sarcophagi, represents the heart of the collection. It is also the main tourist attraction, the reason why millions of visitors have crossed the threshold of the museum.

The statue of Khafre: carved from diorite, it depicts the pharaoh seated on his throne with the Horus falcon protecting him. It is one of the finest examples of royal sculpture from the Old Kingdom.

The Narmer Tablet: a votive tablet and slab, an important Egyptian archaeological find, dated around the 31st century BC, containing some of the oldest hieroglyphic inscriptions ever discovered. It is both an artistically valuable artifact and an extraordinary historical find, effectively marking the beginning of the Egyptian era.

The Royal Mummies: Although many have now been transferred to the National Museum of Egyptian Civilization, the Tahrir Museum remained for decades the place where one could admire the embalmed bodies of the pharaohs, from Ramesses II to Seti I. The experience, of strong emotional impact, fueled a fascination with the preservative power of Egyptian techniques.

The Merneptah Stele: famous for containing the oldest mention of the name “Israel”, it constitutes a key document in biblical history.

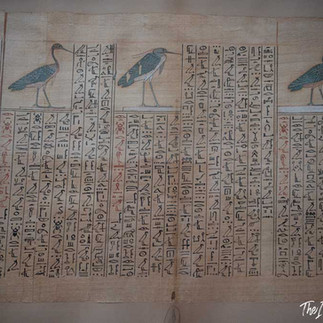

The Papyrus Collection: an extraordinary repository of literary, religious and administrative texts, which testify to the richness of Egyptian written culture.

These pieces are not simple artifacts: they are global icons, which have become symbols of ancient Egypt itself and its perennial capacity to amaze.

The Narmer Tablet

The so-called Narmer Tablet , in green schist, dating back to around 3100 BC, is one of the most emblematic artefacts of early Egyptian art; it is appropriately located near the museum entrance and is the first work I recommend examining, not only for the sculptural quality of the artefact, which wears its 5,000-year age very well, but also for its historical and archaeological importance.

The work, approximately 64 cm tall, was conceived as a ceremonial object, not for practical use, unlike common cosmetic palettes. The composition already reveals what would become the canonical visual grammar of pharaonic art: the ruler depicted on a hierarchical scale (that is, not in natural perspective, but in dimensions proportionate to his importance), captured in the act of subduing his enemy, the use of hierarchical perspective and narrative register, the synthesis of political symbolism and artistic form. On the obverse, Narmer appears wearing the white crown of Upper Egypt, while on the reverse he wears the red crown of Lower Egypt: a duplicity that alludes to the complete unification of the Two Lands under a single authority.

From an archaeological perspective, the tablet is a key document: it provides the earliest figurative representation of a pharaoh identifiable by name, marks the founding moment of Egyptian kingship, and demonstrates the use of art as a tool for political and religious legitimacy. Narmer was the first pharaoh of the First Dynasty; the Narmer Tablet can be considered the founding monument of dynastic Egypt.

Beyond its formidable historical importance and artistic quality, it is nevertheless a work of great fascination; a careful reading reveals the birth of a bloodthirsty militaristic kingdom that marked history and ruled for millennia, along with protohistoric motifs that have their roots even further back, such as the snake-necked serpopards.

Tutankhamun

Once you've devoted enough time to the Narmeer Tablet, you can't help but immediately visit the star of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo: King Tut. His collection is located on the first floor; take the stairs leading up to the first floor and walk along the corridor to the other end of the palace. The first formidable artifact you'll encounter, immediately outside the room housing the boy king's other, more famous grave goods, is the Golden Throne. It's a sensational work, which undeservedly doesn't enjoy the same fame as the Golden Mask or the Sarcophagus.

Crafted of wood covered in gold leaf and embellished with glass paste, lapis lazuli, and semi-precious stones, the throne is striking for its elegant structure and the vibrant colors it retains today. The backrest depicts a delicate scene: Tutankhamun sits relaxed while Queen Ankhesenamun, in a gesture of intimacy surprising for pharaonic art, applies ointment to his shoulders. The iconography, far from being purely ornamental, reveals the private and almost affectionate dimension of the royal couple, in a visual language that blends royalty and everyday life. The technical details—the lion-shaped armrests, the footrests decorated with trampled enemies, the polychrome falcon wings enveloping the throne—testify to the extreme skill of the 18th Dynasty craftsmen and make the piece not only a masterpiece of goldsmithing but also a precious document of the artistic sensibility of the Amarna period, still imbued with naturalism and a taste for the representation of family intimacy.

Tutankhamun's golden throne is not only an artistic masterpiece, but also a precious testimony to the historical phase in which it was created: the delicate transition from Akhenaten's religious experiment to the restoration of traditional cults under the young Tutankhamun.

The scene depicted on the backrest, with Queen Ankhesenamun anointing the pharaoh's shoulders, still recalls the Amarna aesthetic: domestic intimacy, spontaneous gestures, attention to naturalistic details. These traits, unprecedented in Egyptian royal iconography until Akhenaten, reveal how the artistic sensibility of the period continued to be influenced by the Amarna revolution. Yet, the throne is not a "heretical" artefact. The presence of Horus the falcon , protector of royalty, and the symbols of dominion (lions, subdued enemies) clearly signal a return to the consolidated iconographic tradition, in which the pharaoh is the guarantor of cosmic order (Maat) and the victorious lord over foreign peoples.

The throne thus reflects an ideological compromise: on the one hand, it retains the taste for private and almost emotional representation introduced by Akhenaten and Nefertiti; on the other, it reaffirms the elements of divine and political legitimacy functional to the theological restoration desired by the high priests of Amun. It is significant that Tutankhamun, having ascended the throne at a very young age, changed his name from Tutankhaten ("living image of Aten") to Tutankhamun ("living image of Amun"), marking the definitive abandonment of the monotheistic cult of Aten.

In this sense, the throne is not merely a royal ornament, but a visual political manifesto: a declaration in gold and precious stones that the sovereign and his consort, though immersed in a private dimension, were firmly rooted in traditional religion. The blend of intimacy and power, of Amarna-esque naturalism and classical symbolism, captures with rare effectiveness that transitional moment when Egypt sought to close Akhenaten's revolutionary and heretical parenthesis without completely dispersing the artistic legacy he introduced.

Placing the throne outside the small, dark room housing Tutankhamun's most celebrated treasures seems to me to be a clever museum choice, gradually preparing the visitor for what awaits them just ahead. As I've said, the throne is a stunning work that would be much more renowned if it hadn't had the unfortunate fortune of being part of a collection that included even more astonishing works, and I'm referring, of course, in particular, to Tutankhamun's celebrated golden mask. Placing the throne outside the room, at its entrance, gradually prepares the visitor for the shock of seeing one of the most sensational, dazzling, astonishing, disconcerting, and hypnotic works ever created.

I was left speechless and astonished by Tutankhamun's golden mask, as I have been by few other works of art in the world. The goldsmith's skill in creating such a valuable work over 3,000 years ago is breathtaking. The allure of the monarch's face, immortalized for eternity in its childlike features, is profound and hypnotic. The quality of the workmanship is incomparable to other masks preserved in the museum (in the gallery below, alongside some photos of Tutankhamun's mask, I've included a photo of the mask of King Psusennes I, which, despite being a remarkable find, paled in comparison to the more famous golden mask and is completely ignored by visitors who pass by without even a glance). But contemplating the work, it's natural to wonder what other astonishing works this civilization produced, which have been lost to time and have never reached us. Likewise, it comes naturally to wonder who was the unknown, formidable artist who created this immense work 3,000 years ago, only to be later condemned to oblivion by History, which would more meritoriously have placed his name in the collective memory alongside other giants like Michelangelo, Bernini, or Cellini.

In August, the low season for Cairo and Egypt, contrary to my dire predictions, the Golden Mask was not mobbed by hordes of tourists intent on taking selfies; the room was, yes, crowded, but not so crowded that one could not enjoy the work at one's leisure, even for dozens of minutes. From this perspective, kudos also goes to the museum authorities, who have imposed a strict "no photography" policy inside this room. This obviously presents some problems. On the one hand, for me, a photography enthusiast, not being able to photograph the mask except furtively with a few clumsy snaps, was an unbearable constraint; furthermore, the "no photo rule" means having to contemplate the work disturbed by the constant shouts of "no photo inside" from the guards, who simultaneously clandestinely solicit tourists to pay bribes to temporarily suspend surveillance. but the undeniable advantage is the protection of the work from selfie idiots.

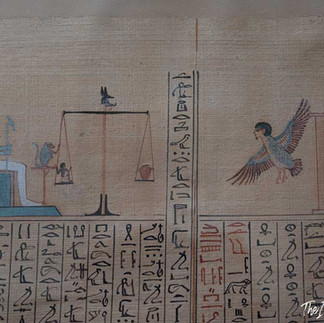

Tutankhamun's golden funerary mask, 54 cm tall and weighing approximately 11 kg, is perhaps the most famous artifact of Egyptian art, but its significance transcends aesthetic impact. Crafted of solid gold inlaid with lapis lazuli, carnelian, obsidian, turquoise, and glass paste, the mask was not merely an ornamental object, but a ritual device intended to ensure the ruler's eternity. Gold, an incorruptible metal, alluded to the flesh of the gods, while the semiprecious stones evoked cosmic values: the blue of lapis lazuli recalled the sky and infinity, the red of carnelian the vital power of the sun. The iconography is rigorously canonical: an idealized face, a blue and gold-striped nemes, a uraeus and vulture on the forehead as symbols of Upper and Lower Egypt, and a braided false beard to indicate the deceased king's divinity. But beyond its formal perfection, the mask plays a crucial historical role: it represents the material translation of the Egyptian conception of kingship as an eternal and superhuman entity. Recent analyses have also suggested that the mask was originally conceived for another person, perhaps a queen, then adapted for Tutankhamun, reflecting the hasty nature of his burial. In this tension between technical refinement, religious significance, and historical contingencies, the mask proves not only an aesthetic masterpiece, but also an irreplaceable document for understanding the funerary and political mentality of New Kingdom Egypt.

King Tut's Hall also contains other treasures, most notably the two sarcophagi, one made of gold-plated wood, and the other of solid gold (a brief pause to reflect on the sarcophagus made entirely of solid gold). The gold sarcophagus is another astonishing work, its fame, like the throne, overshadowed by the mask; again, I can only publish a furtively smuggled photo. Like the mask, the gold sarcophagus is a work of astonishing quality and dazzling beauty and richness (not only in the material sense). In my opinion, it deserves to be placed upright in the middle of the room, rather than supine, which forces a lateral view. Nonetheless, it too is a captivating work, and I recommend taking the time to peruse every fine detail of decoration and goldwork on this priceless artifact with a thousand-year history.

I may dedicate an entire post to King Tut's treasure in the future; for now, I'll just mention that I haven't yet been struck by Tutankhamun's infamous curse, which I'll elaborate on if I ever decide to write a whole post about it. However, after contemplating Tutankhamun's treasure, I suffered from diarrhea for weeks, and the more superstitious might think that it wasn't due to Cairo's food and water system.

I mentioned above the gold mask of Psusennes I, located in a room adjacent to that of Tutankhamun, as a lesser comparison to the exquisite quality of the gold mask. One final mention, before moving on to other works, I think also deserves the silver sarcophagus of Psusennes I. Just as I mentioned the mask's unknown creator and the iniquity with which history has treated his memory, I think Psusennes himself deserves mention for the modest fortune history has reserved for him. In ancient Egypt, in fact, silver was a much rarer and more precious material than gold, which the various dynasties plundered in abundance from neighboring Nubia for centuries. Contemplating the sarcophagus of Psusennes, crafted with extreme finesse entirely of silver, I wonder how furious he must be, after thousands of years, towards the child pharaoh who, reigning for only a few years, and having a funerary outfit made for himself in base gold, enjoys, after thousands of years, a fame immeasurable in comparison to that of the relatively unknown Psusennes I.

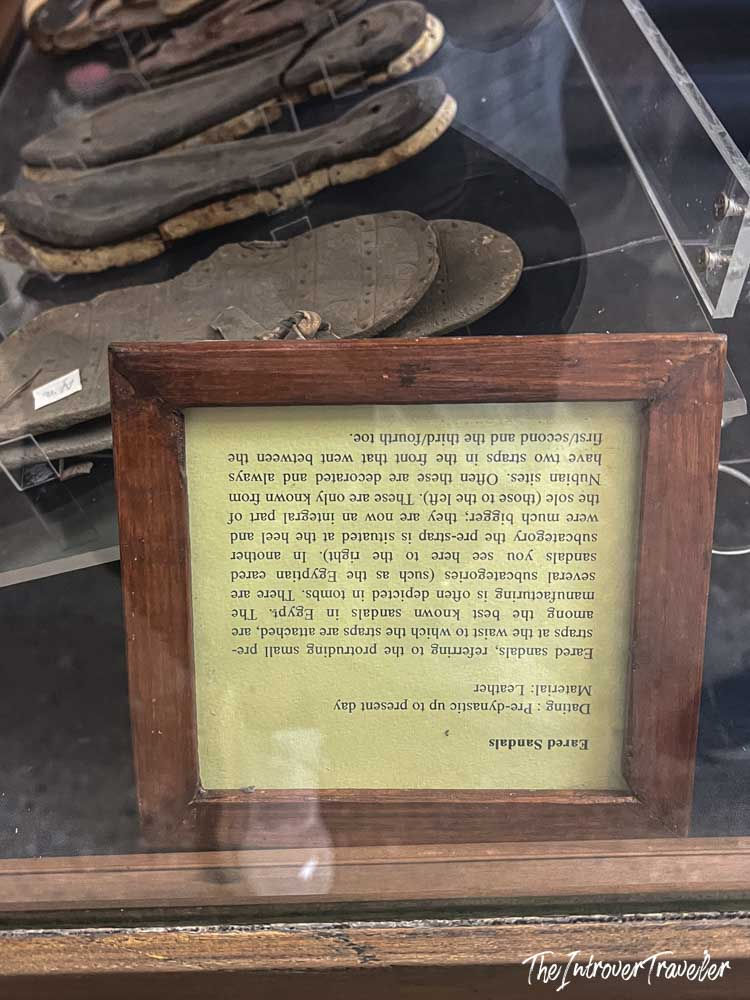

To complete this post, I'm publishing below some photographs of some notable works, among which I feel it's necessary to at least mention the statue of Khafre, which I mentioned above. The museum isn't limited to the Narmeer tablet and Tutankhamun's treasure; there are obviously many other artifacts of artistic and historical value that might be of interest to visitors who, like me, lack specific and in-depth knowledge of Egyptian art. And, of course, there are thousands of artifacts of no artistic value and of exclusively historical and archaeological interest: hundreds of identical canopic jars, footwear, wigs, indecipherable papyrus, work tools, more or less anonymous artifacts, statues and stelae of secondary importance, mummies of monarchs and animals. At times, boredom inevitably sets in, unless it's occasionally roused by a work of art that stands out for its craftsmanship or exotic interest.

The current state: grandeur and decadence

However, the progressive state of decay characterizing the Tahrir Square museum cannot be ignored. The rooms often appear poorly lit, the display of objects is dense to the point of claustrophobia, the captions are outdated, difficult to read, and rarely updated. Many display cases appear worn, some not even guaranteeing optimal conservation conditions. Dust is everywhere, many display cases look as if they haven't been cleaned in a century; currently, the museum feels more like a construction site than a cultural institution, and I can't say how much of this is due to the ongoing relocation to the new GEM.

For visitors accustomed to European or American museum standards, the experience can be disconcerting: a chaotic display that risks overshadowing the magnificence of the works. The museum feels more like a monumental repository than an educational institution capable of communicating the pharaonic civilization in a clear and engaging way.

The criticisms are not new. Already in the 1960s and 1970s, scholars and travelers pointed out the need for radical modernization. However, economic difficulties, bureaucracy, and the political context have made any renovation nearly impossible. The result is that today the museum appears as a museographic relic, interesting not only for its collections but also as a testament to a 19th-century approach to museology.

Tips for visiting

Despite its structural limitations, a visit to the Egyptian Museum remains an essential experience for anyone visiting Cairo. Here are some practical tips:

Arrive early: the crowds are often huge, especially in the halls dedicated to Tutankhamun. Visiting in the morning allows you to enjoy a relatively quieter atmosphere, before the contents of the large buses are regurgitated into the halls.

Prepare in advance: I'm not a fan of tour guides, who usually limit themselves to stun tourists with a few anecdotes and trivia of dubious value; however, Egyptian archaeology and art are particularly obscure and impenetrable, so a little preliminary study that allows you to at least recognize the main iconographic elements can benefit your visit.

Take your time: unlike what I said for example about the MET, where I had to skip the entire Egyptian section to be able to complete the visit in a single day, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is not huge and can be visited entirely in half a day without sacrificing any works, so come when it opens and calmly walk through the museum, lingering for as long as necessary on the works that most interest you.

Prepare for contrast: don't expect a glittering museum perfectly aligned with international standards. The experience itself has an almost "archaeological" quality: it feels like entering a 19th-century warehouse, and this can also be particularly fascinating for those who appreciate its atmosphere.

Considering the future: With the opening of the GEM, a visit to the Tahrir Museum takes on the added value of a historical document. Visiting today (late 2025) means seeing the institution in its original form, before it is inevitably downsized.

A critical reflection

The Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square is a perfect metaphor for contemporary Egypt: grandiose in its heritage, fragile in its structures, suspended between glory and decadence. Its very survival, miraculously avoided by looting and inadequate maintenance, speaks volumes about the country's difficulties in valorizing its heritage.

One might criticize the Egyptian authorities for failing to invest in a serious modernization of the museum, for allowing such a prestigious institution to become a dusty dump. But it would also be unfair to forget that Egypt has faced economic crises, revolutions, terrorism, and political instability: in such a context, the priority of culture has often been sacrificed.

However, the feeling remains that Egypt hasn't fully grasped the strategic value of its heritage. If well preserved and enhanced, it could be not only a source of identity pride, but also a huge economic driver. Instead, the impression one gets from visiting Tahrir is one of squandered grandeur, of cultural capital left to languish.

Conclusion: a monument to memory, rather than a museum for the future

Today, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is at a crossroads. With the opening of the GEM, it risks losing much of its most celebrated collections. It could become a "minor" museum, or reinvent itself as a historic institution, preserving the charm of a place that defined an era of archaeology.

In any case, it remains a fundamental place to visit, not only for the treasures it holds, but because it bears witness to the complexity of Egypt's relationship with its past. Strolling through its halls is like traversing a palimpsest of memories: on the one hand, the immortality of the pharaohs, on the other, the fragility of modern institutions.

Those who cross the threshold of the Tahrir Square museum don't simply enter an exhibition of antiquities: they enter a political, historical, and cultural narrative that concerns both Egypt and the West. And it is perhaps this layering of meanings, even more than the gold and stone treasures, that makes the museum an essential experience for anyone who truly wants to understand what "Egypt" means in the contemporary world.

Comments